|

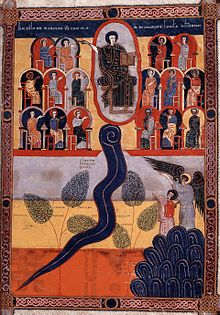

| Ancient of days icon: see Daniel 7:13-14 |

Psalm 117: Sunday Lauds

Vulgate

|

Douay-Rheims

|

Alleluja.

|

Alleluia.

|

Confitémini Dómino quóniam

bonus: * quóniam in sæculum misericórdia ejus.

|

Give praise to the Lord, for he

is good: for his mercy endures for ever.

|

2 Dicat nunc Israël quóniam bonus: * quóniam in

sæculum misericórdia ejus.

|

2 Let Israel now say, that he

is good: that his

mercy endures for ever.

|

3 Dicat nunc domus Aaron: * quóniam in sæculum misericórdia

ejus.

|

3 Let the house of Aaron now say, that his

mercy endures for ever.

|

4 Dicant nunc qui timent

Dóminum: * quóniam in sæculum misericórdia ejus.

|

4 Let them that fear the Lord now say, that his

mercy endures for ever.

|

5 De tribulatióne invocávi Dóminum: * et exaudívit me

in latitúdine Dóminus.

|

5 In my trouble I called

upon the Lord: and

the Lord heard me,

and enlarged me.

|

6 Dóminus mihi adjútor: * non timébo quid fáciat mihi

homo.

|

6 The Lord is my helper: I

will not fear what man

can do unto me.

|

7 Dóminus mihi adjútor: * et ego despíciam inimícos meos.

|

7 The Lord is my helper: and

I will look over my enemies.

|

8 Bonum est confídere in Dómino: * quam confídere in hómine.

|

8 It is good to confide in the Lord, rather than to

have confidence in man.

|

9 Bonum est speráre in

Dómino: * quam speráre in princípibus.

|

9 It is good to trust in the Lord, rather than to

trust in princes.

|

10 Omnes Gentes circuiérunt me: * et in nómine Dómini

quia ultus sum in eos.

|

10 All nations compassed me

about; and, in the name

of the Lord I have

been revenged on them.

|

11 Circumdántes

circumdedérunt me: * et in nómine Dómini quia ultus sum in eos.

|

11 Surrounding me they

compassed me about: and in the name of the Lord I have been

revenged on them.

|

12 Circumdedérunt me

sicut apes, et exarsérunt sicut ignis in spinis: * et in nómine Dómini quia

ultus sum in eos.

|

12 They surrounded me like

bees, and they burned like fire among thorns: and in the name of the Lord I was revenged on

them.

|

13 Impúlsus evérsus sum ut cáderem: * et Dóminus suscépit me.

|

13 Being pushed I was

overturned that I might fall: but the Lord supported me.

|

14 Fortitúdo mea, et

laus mea Dóminus: * et factus est mihi in salútem.

|

14 The Lord is my strength and

my praise: and he has become my salvation.

|

15 Vox exsultatiónis,

et salútis: * in tabernáculis justórum.

|

15 The voice of rejoicing

and of salvation is

in the tabernacles of the just.

|

16 Déxtera Dómini

fecit virtútem: déxtera Dómini exaltávit me, * déxtera Dómini fecit virtútem.

|

16 The right hand of the Lord has wrought

strength: the right hand of the Lord has exalted me:

the right hand of the Lord

has wrought strength.

|

17 Non móriar, sed vivam: * et narrábo ópera Dómini.

|

17 I shall not die, but

live: and shall declare the works of the Lord.

|

18 Castígans castigávit

me Dóminus: * et morti non trádidit me.

|

18 The Lord chastising has

chastised me: but he has not delivered me over to death.

|

19 Aperíte mihi

portas justítiæ, ingréssus in eas confitébor Dómino: * hæc porta Dómini,

justi intrábunt in eam.

|

19 Open to me the gates of justice: I will go in

to them, and give praise to the Lord 20 This is

the gate of the Lord,

the just shall enter

into it.

|

20 Confitébor tibi

quóniam exaudísti me: * et factus es mihi in salútem.

|

21 I will give glory to you because

you have heard me: and have become my salvation.

|

21 Lápidem, quem

reprobavérunt ædificántes: * hic factus est in caput ánguli.

|

22 The stone which the

builders rejected; the same has become the head of the corner.

|

22 A Dómino factum est

istud: * et est mirábile in óculis nostris.

|

23 This is the Lord's doing, and it is

wonderful in our eyes.

|

23 Hæc est dies, quam

fecit Dóminus: * exsultémus et lætémur in ea.

|

24 This is the day which

the Lord has made:

let us be glad and rejoice therein.

|

24 O Dómine, salvum me fac, O Dómine, bene prosperáre: *

benedíctus qui venit in nómine Dómini.

|

25 O Lord, save me: O Lord, give good success. 26 Blessed be he that

comes in the name of

the Lord.

|

25 Benedíximus vobis de domo Dómini: * Deus Dóminus, et

illúxit nobis.

|

We have blessed you out of the house of the Lord.

27 The Lord is God, and he has shone

upon us.

|

26 Constitúite diem

solémnem in condénsis, * usque ad cornu altáris.

|

Appoint a solemn day, with shady

boughs, even to the horn

of the altar.

|

27 Deus meus es tu, et confitébor tibi: * Deus meus es tu, et

exaltábo te.

|

28 You are my God, and I will praise

you: you are my God,

and I will exalt you.

|

28 Confitébor tibi quóniam

exaudísti me: * et factus es mihi in salútem.

|

I will praise you, because you

have heard me, and have become my salvation.

|

29 Confitémini Dómino

quóniam bonus: * quóniam in sæculum misericórdia ejus.

|

29 O praise the Lord, for he is good: for his mercy

endures for ever.

|

Psalm 117 is the last of the 'Hallel' psalms sung on major feasts in the Jewish liturgy, it contains a number of key verses that Our Lord made clear applied to him, above all verse 22.

The reasons for its use on Sunday are fairly clear cut: Fr Pius Pasch's early twentieth century breviary commentary, for example, says:

In the earlier version of the Roman Office from which St Benedict may have borrowed, though, Psalm 117 was probably said at Prime rather than Lauds. If this was the case, why did he shift it to Lauds, particularly given its lack of overt references to dawn and the morning?

Christ the true day

One possibility seems to me to be the reference to Christ as the day (latin: dies, diei) in verse 24.

Christ as the day was a favourite theme of the Fathers. St Cyprian's instruction on prayer for example, include the following:

And on this basis, one of the key themes reflected in several of the first variable psalms each day is the reference to entering heaven to praise God in verses 19-20:

The key themes of the psalm

The reasons for its use on Sunday are fairly clear cut: Fr Pius Pasch's early twentieth century breviary commentary, for example, says:

Festival hymn. In this psalm, a celebrated liturgical hymn of the ancient synagogue (also a thanksgiving hymn on the feast of Tabernacles), we sing our Easter joy occasioned by the Resurrection of our Lord and our own spiritual resurrection in him.It has some very clear links to the traditional canticle of the day as well (which I'll go into a little more below).

In the earlier version of the Roman Office from which St Benedict may have borrowed, though, Psalm 117 was probably said at Prime rather than Lauds. If this was the case, why did he shift it to Lauds, particularly given its lack of overt references to dawn and the morning?

Christ the true day

One possibility seems to me to be the reference to Christ as the day (latin: dies, diei) in verse 24.

Christ as the day was a favourite theme of the Fathers. St Cyprian's instruction on prayer for example, include the following:

But for us, beloved brethren, besides the hours of prayer observed of old, both the times and the sacraments have now increased in number. For we must also pray in the morning, that the Lord's resurrection may be celebrated by morning prayer.

And this formerly the Holy Spirit pointed out in the Psalms, saying, My King, and my God, because unto You will I cry; O Lord, in the morning shall You hear my voice; in the morning will I stand before You, and will look up to You. And again, the Lord speaks by the mouth of the prophet: Early in the morning shall they watch for me, saying, Let us go, and return unto the Lord our God...

Moreover, the Holy Spirit in the Psalms manifests that Christ is called the day. The stone, says He, which the builders rejected, has become the head of the corner. This is the Lord's doing; and it is marvellous in our eyes. This is the day which the Lord has made; let us walk and rejoice in it.

Also the prophet Malachi testifies that He is called the Sun, when he says, But to you that fear the name of the Lord shall the Sun of righteousness arise, and there is healing in His wings. But if in the Holy Scriptures the true sun and the true day is Christ, there is no hour excepted for Christians wherein God ought not frequently and always to be worshipped; so that we who are in Christ— that is, in the true Sun and the true Day— should be instant throughout the entire day in petitions, and should pray; and when, by the law of the world, the revolving night, recurring in its alternate changes, succeeds, there can be no harm arising from the darkness of night to those who pray, because the children of light have the day even in the night. For when is he without light who has light in his heart? Or when has not he the sun and the day, whose Sun and Day is Christ?The references to dawn and morning light in many of the psalms of Lauds then, were not just selected for their references to morning prayer, but perhaps on the basis that they were seen by the Fathers as containing references to the Resurrection, the true day of the world.

And on this basis, one of the key themes reflected in several of the first variable psalms each day is the reference to entering heaven to praise God in verses 19-20:

Open to me the gates of justice: I will go in to them, and give praise to the Lord This is the gate of the Lord, the just shall enter into it.As we shall see this week, all of the first variable psalms of Lauds contain similar references - it is most explicit in Psalms 5, 42 and 75.

The key themes of the psalm

Cassiodorus summarises the structure of the psalm as follows:

The faithful people are freed from the bonds of sins, and in the first section they offer a general exhortation that each of us should confess to the Lord, for they have gained a hearing in afflictions, and have proclaimed that no man whatsoever is to be held in fear.

In the second part they say that we must have confidence in the Lord alone, through whom they know that they have escaped the enmity of the Gentiles, and have attained the remedies of a truly genuine life.

In the third section they say that the gates of justice are to be opened; they speak there also of the Cornerstone which is Christ the Saviour.

In the fourth, they persuade the other Christians that they must crowd the Lord's halls in shared joy and sweet delight at the coming of the holy incarnation.Latin word study: confess and praise the Lord

This psalm has lots of litany-esq repetitions, making it easier to memorise, so let me first point out a few key words in the opening litany section

Confitemini, the opening word of this psalm is actually quite key to the themes of Lauds I think. The word literally means let us confess, and comes from the same verb used in confession of sins, viz confiteor, fessus sum, eri. It has both a positive connotation (to praise, give thanks) and a negative one (to confess, acknowledge one's guilt), and both are implied here and throughout this series of psalms I think.

In fact Daniel 3 (from whence the Sunday canticle, the Benedicite cometh, another reason, presumably for the shift of the psalm to Lauds) provides the phrase spelt out in exactly that way:

[89] Confitemini Domino, quoniam bonus: quoniam in saeculum misericordia ejus. [90] Benedicite, omnes religiosi, Domino Deo deorum: laudate et confitemini ei, quia in omnia saecula misericordia ejus.

[89] O give thanks to the Lord, because he is good: because his mercy endureth for ever and ever. [90] O all ye religious, bless the Lord the God of gods: praise him and give him thanks, because his mercy endureth for ever and ever.

In the pslams that follow, this theme is, I think expanded in this way: God confronts us with the truth (veritas, veritatis) about ourselves which we must acknowledge and ask for his mercy (misericordia -ae); those who refuse to do that will be subject to his justice (justitia).

It's the same key theme as in Psalm 129 (Tuesday Vespers):

3 Si iniquitátes observáveris,

Dómine: * Dómine, quis sustinébit?

|

3 If you, O Lord, will mark iniquities: Lord, who shall stand it.

|

4 Quia apud te propitiátio est: * et propter legem tuam

sustínui te, Dómine.

|

4 For with you there is

merciful forgiveness: and by reason of your law, I have waited for you, O Lord.

|

7 Quia apud Dóminum

misericórdia: * et copiósa apud eum redémptio.

|

So make that key refrain your own:

Confitémini Dómino quóniam bonus:

Dicat nunc Israël (the Church) quóniam bonus: Dicat nunc domus Aaron (the priests): Dicant nunc qui timent Dóminum (the faithful): |

quóniam in sæculum misericórdia ejus.

|

Scriptural and liturgical uses

|

NT references

|

Rom 8:31,

Heb 13:6 (v6);

Lk 1:51 (v16);

Rev 22:14 (v19);

Jn 10:9 (v20);

Mt 21:42,

Acts 4:11,

1 Cor 3:11,

Eph 2:20,

1Pet 2:4-7 (v21);

Mt21: 9-14, 23-39 (v24)

|

|

RB cursus

|

Sunday Lauds

|

|

Feasts, antiphons etc

|

AN: 3297 (5); 1745

(5); 1809 (11);

3289, 3290, 5509

(15);3577 (v22-3); 2997

(v24); 4024 (25);

4117 (25-6); 2175(28)

|

|

Roman pre 1911

|

Sunday Prime

|

|

Roman post 1911

|

1911-62: Lauds II . 1970:

|

|

Responsories

|

Epiphanytide Friday v28; 6073, 6799 (v24,

Haec dies)

|

|

Mass propers (EF)

|

Nativity Aurora GR

(23, 26, 27)

Lent 2 TR (v1=105)

Lent 3 Tues OF

(16-17);

Lent 4 Friday GR

(8-9);

Passion I OF (17, ),

Maundy Thurs OF

(16-17);

Easter Vigil AL (1);

Easter Day GR (1,

23),

Easter Mon GR (2, 24)

Easter Tues IN v(1),GR

(24,3)

Easter Wed GR (24,

16)

Easter Thurs GR

(23,21,22);

Easter Fri GR (23,

24-5);

Easter Sat AL 23, OF

24-25;

Eastertide 4 AL (16);

PP14 GR (8-9).

Finding holy Cross

May 3: OF (5,6, 16, 17)

|

You can find some of my previous notes on this psalm here.

And you can find the next part in this series here.