|

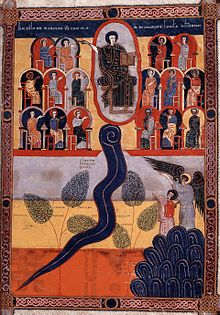

| The New Jerusalem and the River of Life (Apocalypse XII), Beatus de Facundus, 1047 |

So far in this series I've talked about the overall structure and context of Lauds; today I want to start on the main focus of this series, the variable psalms of the hour.

The variable psalms St Benedict uses for the hour are Psalms 5, 35, 42, 56, 62, 63, 64, 75, 87, 89, 91, 117 and 142.

Relationship to the Roman Office?

Some, but not all of these psalms also feature in the later Roman Office - that Office though, only had one variable psalm each day, and St Benedict doesn't use all of those; nor does he use them on the same days as the Roman Office.

This presents something of a puzzle, since although St Benedict lists out all of the psalms to be said each day (in contrast to the variable canticles where he just says use the Roman ones), he also describes them as the customary psalms:

Post quem alii duo psalmi dicantur secundum consuetudinem, id est...

After these, two other psalms are to follow, according to established usage; thus...Established use, or customary where? In his monastery? In some Roman monastery whose Office has subsequently vanished? We will perhaps never know.

Purely mechanistic?

At least some of these psalms do have a history in association with Lauds though.

Two of the thirteen psalms St Benedict uses - viz Psalms 5 and 62 - have a long tradition of association with the hour behind them, attested to as early as Origen in the second century, and so their use is readily explicable.

Five more - Psalms 42, 64, 89, 91 and 142 - feature in the later Roman Office and most commentators now assume he borrowed them from a primitive version of the Roman Office.

If that was the case though, the Roman practice at this hour (assuming it really was settled at this time, a proposition for which there is no hard evidence) cannot have been the definitive criterion for their use for several reasons

First, St Benedict doesn't use two of the Lauds psalms of the Roman Office viz Psalms 92 and 99,in his Office (the current 'festal' version of Lauds is a later addition which I will look at briefly at the end of this series).

Secondly, St Benedict frequently displays a willingness to move psalms between hours (such as shifting Psalms 1-2 and 6-19 out of Matins and 119-125 out of Vespers), and between days (Psalm 91 is said on Saturday in the Roman Office, on Fridays in the Benedictine, and vice-versa for Psalm 142). In the case of Lauds, for example, he doesn't just take psalm from the Matins sequence but also Psalm 117 which in the later Roman Office was said at Prime (though probably was originally located at Vespers). Similarly, Psalm 53 may have formed part of Roman Prime at this time, but St Benedict places it in Matins.

Still, if we accept their use in the Roman Office as the rationale for their inclusion for the moment, we still have to explain the choice of six additional psalms, Psalms 35, 56, 63, 75, 87 and 117 (and the reasons for the initial rejection and later acceptance of Psalms 92 and 99 in the Benedictine cursus).

Morning prayer?

One possible explanation is that St Benedict selected the variable psalms for Lauds on the basis of their references to morning prayer and/or the light of dawn.

Certainly the two Roman Office psalms that St Benedict excludes from his version of the hour don't contain any explicit references to these themes, while the ones he selects do. The table below summarises the key references in question sometimes cited (for example in Hildemar's c850 commentary on the Rule).

Monday

|

O Lord, in the morning you shall hear my voice In the morning I will stand before you (Ps 5: 3-4)

|

and in your light we shall see light (Ps 35:10)

| |

Tuesday

|

Send forth your light and your truth (Ps 42:3)

|

Arise, O my glory, arise psaltery and harp: I will arise early (Ps 56:11)

| |

Wednesday

|

you shall make the outgoings of the morning and of the evening to be joyful (Ps 64:8)

Shall your wonders be known in the dark (Ps 64:13) |

Thursday

|

But I, O Lord, have cried to you: and in the morning my prayer shall prevent you. (87:14)

|

In the morning man shall grow up like grass; in the morning he shall flourish and pass away (89:6)

our life in the light of your countenance (89:8) We are filled in the morning with your mercy: and we have rejoiced, and are delighted all our days (89:16) And let the brightness of the Lord our God be upon us (89:17) | |

Friday

|

You enlighten wonderfully from the everlasting hills (75:4)

|

To show forth your mercy in the morning (91:2)

| |

Saturday

|

Cause me to hear your mercy in the morning; for in you have I hoped (142: 9)

|

Sunday

|

O my God, to you do I watch at break of day (62:1)

I will meditate on you in the morning (62:7)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Lord is God, and he has shone upon us (117:27)

|

Does this listing fully explain his choices however?

Well no, not in my opinion.

First, Psalm 63 on Wednesday has no obvious references to light or morning at all.

Secondly, while Psalm 117 does contain a reference to light, it is not obviously to dawn or morning prayer. And several of the other references seem somewhat tenuous on the face of it.

Thirdly, and most importantly perhaps, there are actually quite a few other psalms that St Benedict could have selected for this purpose.

If we ignore the psalms of the Vespers cycle (though in reality, there is no good reason to, since St Benedict shifted several of them to Terce to None!), and just look at the (Roman) Matins sequence in particular that meet this criteria of strong references to morning and light and could have been allocated to Lauds - many of them (including Psalms 17, 18, 26, 29, 45, 73, 77, 106 and 107) with rather stronger claims than those St Benedict actually uses.

Psalms 17&18 have key places in Prime, so we can eliminate them from consideration, and Psalms 73, 77 and 106 might perhaps have been deemed too long for the hour.

But consider these possibilities, all of which fit with the prayer while awaiting the Resurrection/Christ as light theme:

- The Lord is my light and my deliverance; whom have I to fear? (Ps 26)

- sorrow is but the guest of a night, and joy comes in the morning (Ps 29)

- But the city of God, enriched with flowing waters, is the chosen sanctuary of the most High, God dwells within her, and she stands unmoved; with break of dawn he will grant her deliverance (ps 45); and

- Wake, my heart, wake, echoes of harp and viol; dawn shall find me watching (Ps 107).

Another curious feature of the Lauds psalms is how St Benedict allocates them to the particular day of the week and place in the hour. The table below shows which psalm is said on each day.

Sunday

|

Monday

|

Tuesday

|

Wednesday

|

Thursday

|

Friday

|

Saturday

|

Matins:20-31

|

Matins: 32-44

|

Matins: 45-58

|

Matins:

59-72

|

Matins:

73-84

|

Matins: 85-100

|

Matins: 101-108

|

Ps 117

|

Ps 5

|

Ps 42

|

Ps 63

|

Ps 87

|

Ps 75

|

Ps 142

|

Ps 62

|

Ps 35

|

Ps 56

|

Ps 64

|

Ps 89

|

Ps 91

|

Deut

|

Benedicite

(Dan 3)

|

Is 12:1-6

|

Is 38:10-20

|

1 Kings 2:1-10

|

Ex 15:1-10

|

Hab 3:2-19

|

32:1-43

|

Note that some psalms (viz Psalms 62, 75 and 117) are used out of their numerical sequences, the only hour of the Benedictine Office at which this occurs (fixed psalms aside).

In addition, unlike the Roman version of this hour, the psalms used at Lauds each day often - viz on Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday don't all sit within the Matins (or other) sequence(s) for the day of the week.

In some cases there is perhaps an explanation for this. Psalm 5, for example, is presumably on Monday because it is the only one missing from the Psalm 1-6 group on that day (Ps 1,2 and 6 being said at Prime, Ps 3&4 at Matins and Compline each day).

In other cases, the reasons for the allocations are less obvious. Why place not place Psalm 142 on Friday, for example, as it was in the later Roman Office, the day it would otherwise have been said at Vespers?

The shaping of Benedictine Lauds

The explanation for the psalm selections for Lauds, I think, reflects several different factors:

- some psalms are left in Matins or removed from the sequence in order to ensure that Matins each day has a thematic coherence - Psalm 45 presumably opens Tuesday Matins, for example, rather than being moved to Lauds because it so clearly states the themes of that day and is important to that particular sequence of psalms;

- there is rather more to the dawn theme than just references to the morning than the simple references might suggest;

- there was a need to ensure that the psalms used each day have a link to the themes of the day suggested by the Old Testament canticles said at Lauds; and

- St Benedict's desire to use psalms that include some common memes - including but not limited to the morning prayer/light theme - that help give the hour and the psalm group a horizontal unity.

The linking theme between them is that in this life God offers us his protection in weathering the attacks of evildoers so that we can endure, best summarised in this line from Psalm 56:

And in the shadow of your wings will I hope, until iniquity pass away.As we look more closely at this group of psalms over the next few weeks I will try and draw out these linkages and themes out more closely.

Latin word study

As we go along in this series, I'm also going to provide some key word prompts for those wanting to become more familiar with the Latin, focusing on key concepts, images and phrases that tend to recur in the psalms and elsewhere in Scripture, particularly those relevant to the key themes of Lauds.

The psalms use a huge vocabulary (4,000 words plus, compared to most people's normal everyday vocabulary of around 1500 words) so are quite challenging to learn (and remember!). So focusing on a few key words each day can help push the learning process on a little!

Next part in the series

In the meantime, continue on to Psalm 117.